A lot of my thinking at the moment is on curriculum and subject knowledge. I profess to be no level of expert on either topic – and am learning all the time about the former – but they have really taken my interest of late.

The more I read about how we learn, I consider the ways in which our curriculum can be reshaped to allow students opportunities to connect new knowledge to existing knowledge and ways in which we can better plan sequences of learning (with emphasis on spaced retrieval/interleaving).

These are huge questions, and not ones that this post seeks to deal with now, but they started a me thinking anew about CPD. This too was further prompted by an article in TES (fairly recently?), focusing on the damning implications of limited subject-specific CPD. The report linked in the article, Developing Great Subject teaching, gave me food for thought. If you don’t have time to go through the full 53 page report, spend some time considering the implication of the headline findings, notably:

Performance review is widely used to identify and balance CPD needs for the school as a whole and for individuals.

The report qualifies the point made:

Primary and secondary schools with a strong CPD offer put a lot of effort into doing this systematically, using different evidence sources and aligning analysis of individual needs with school self-evaluation, improvement and CPD activities.

However, I would suggest that for many teachers, this CPD remains focused on generic pedagogy (excellent article by Michael Fordham on this). Besides this, quality CPD should be an entitlement for teachers.

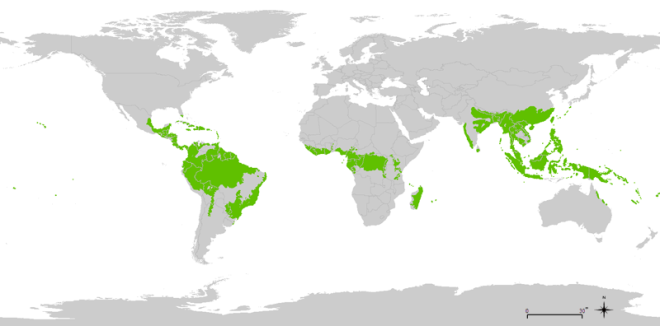

It’s, unfortunately, easy to see why this situation has arisen. There seems to be a lack of quality CPD offers being made to subject-specialists. Of course, I don’t proclaim to speak for all subjects and phases, but when I reflect on my own subject, I worry about the lack of high-quality training that is out there. This carries dangerous implications for the future of geography – the very nature of the subject means it is constantly changing – and if we are not able to access high quality CPD, the quality of our practice suffers.

So, this post comes with a plea – geographers, where are you getting your CPD from? And, perhaps more crucially, how are you able to drill down and share it with your own staff?

For me, my subject knowledge has been fundamentally improved by accessing regular and up to date news outlets, membership of the GA has been truly transformative (would highly recommend if you are able to join) and, of course a number of Twitter colleagues are always linking and sharing new materials related to geography. I, even, go back to the textbooks and materials I was lucky enough to have from my A-Level/university studies – these always give me further threads of thought.