**Following some positive noises on Twitter, delighted to return to #HowITeachGeog! This post is provided by the brilliant @RobboGeog – go and find her on Twitter – who got the writing bug and shared this over. Love it!

Tackling a sensitive and interesting issue here – I think Hina does a great job in unpacking some of the issues and challenges around this topic. Let us know your thoughts #geographyteacher!**

The development gap is one of my favourite topics to teach. It is a really important basis for so many other aspects of geography, including country studies. In the current climate it is important for students to understand where some of the issues might originate from.

The starting point is to understand what the gap is. This can be made more difficult if you are teaching in an area that is not ethnically diverse or if students have not been outside of Europe. However it does need to be done in a way that does not embed stereotypes.

I start with some cartoons to generate discussions. Sometimes these can highlight stereotypes or make generalisations but that is OK as that is something that can be looked at. If it doesn’t come up naturally then it can be done through careful questioning. In one class the cartoon on the left got one girl (with a Nigerian background) particularly angry when she first looked at it as she felt it was a sweeping generalisation of all African countries. It was very important that this was brought up.

We then talk about how we define countries at different ends of the gap, moving away from the basic rich/poor. To visualise life at different levels (something which many students will not have seen personally) I use website such as Dollar Street and the link below:

The key stage you are teaching at may determine the language you use. At key stage 3 I use Hans Rosling’s 4 levels. However at GCSE you may need to stick with the language that the board uses (for example AQA uses HIC/LIC/NEE).

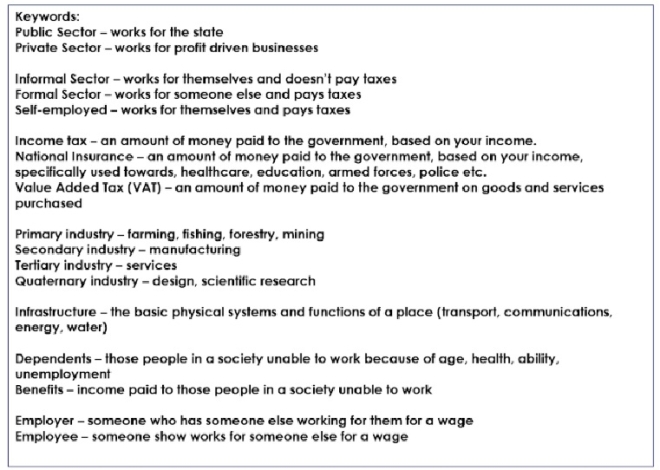

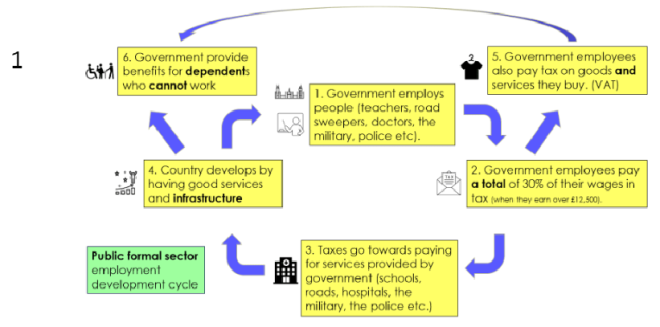

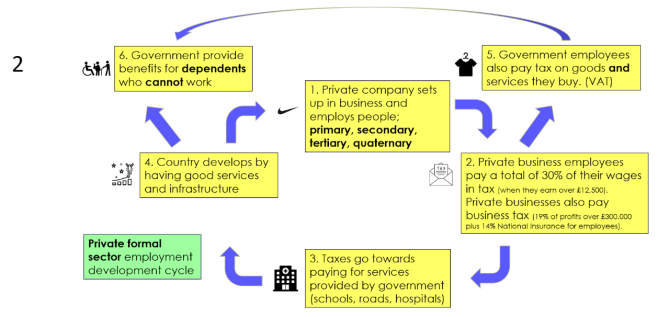

Terminology is key as there are many terms used in this topic – some of which we assume students already know. So I will get students to create a glossary as we go – of mainly level 3 vocabulary but there will be some level 2 vocabulary that needs to be defined as well.

We look at the categories that the causes of the development gap can fall into – historical, environmental and socio-economic. There should not be an assumption that all students will remember these from using them previously so it best to define these.

I will start with the historical and the key factor of colonialisation. Being a British East African Asian myself this is an easy one for me to talk about. Geography teachers need to have the knowledge of what happened and its impacts, which I hope they would be. However with a rising number of non-specialists teaching the subject, especially at key stage 3, subject leads must not assume that they have the same knowledge.

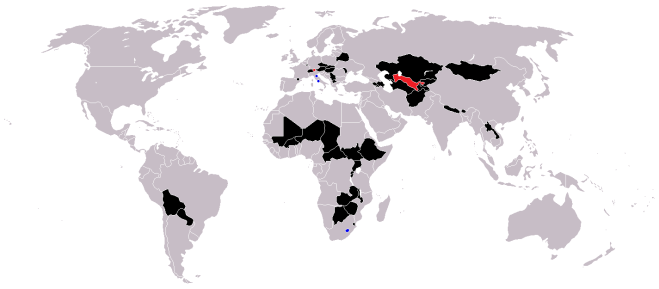

The term colonialisation is likely to be unfamiliar with students though they may have heard of the British Empire or the Commonwealth – but do they know what these actually mean? I do not assume that they do – an explanation is needed (they may not have studied this in history yet). A map is useful here – as is showing that other countries also had their own empires and had the same impacts. Students need to know why countries colonised others and how they were able to in order to understand why this led to the development gap. This can be tricky if you have students from with an ethnic background originating from a Commonwealth country as they can be quite passionate about it. I find it best to utilise them and get them to give their point of view to be discussed. Colonisation led to countries being stripped of their resources for the gain of the colonising countries, in some cases this included people being made into slaves. When countries gained independence many of them struggled to decide who was going to run the country which led to civil wars and dictatorships in many cases. It is important to let students digest this and take questions – make links to areas already studied but also those they will be studying.

Environmental causes are easier to explain as they are not as controversial. I use pictures to get students to think of some ideas themselves, for example:

Students think of geographical questions to ask about the pictures and their link to development – higher ability students will be expected to draw on knowledge gained from previous topics studied (so showing synoptic links). They need to be clearly taught the impact of the different environmental factors. For example a country being susceptible to climate and/or tectonic hazards will struggle to develop as it may lose its crops and therefore income on a regular basis, therefore not have the money to spend on services and improving quality of life (this is a basic explanation). The key here is to ensure a sequenced explanation; i.e. what the environmental factor leads to. There is also the point that there is rarely a stand-alone cause – usually there are few causes linked together. Higher ability students will be expected to link these together.

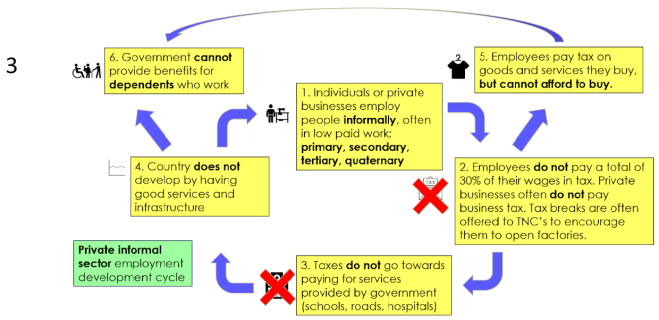

Socio-economic causes can cover a variety of factors, for example war, trade and the poverty trap. Again sequencing is important here. This is another area where an assumption must not be made – students will not necessarily know how trade works so an explanation of this is necessary, maybe through a short YouTube clip (I still think there is a value to the trading game if run properly). The poverty trap really helps students to understand that is not the fault of the people caught in it; they are not lazy and relying on help. Misconceptions must be challenged and pre-empted.